What is Vestibular Migraine?

What is Vestibular Migraine?

Vertigo is a feeling of movement that comes from the Latin word which means “to turn” and is likened to the feeling one has after turning around a number of times and then stopping. It is what one feels on the playground after getting off of a merry go round. With vertigo the involved person is sitting still, yet feels as if the world around him is spinning, or moving.

Migraine is a frequent headache disorder which may be severe and is headache which is usually throbbing, one-sided, and associated with nausea, vomiting, and sensitivity to light and sound. About 40% of persons with migraine may also experience vertigo.

Migraine is found in 12% of persons and is for women, their most common medical problem, occurring in 25% of women and 6% of men.

Read my article, “What is Migraine?” on my website, www.doctormigraine.com.

This is an article by Britt Talley Daniel MD, retired member of the American Academy of Neurology, the American Headache Society, migraine textbook author, and blogger.

Vestibular migraine (VM) is a neurological condition that may come with or without migraine headache where the person experiences vertigo, dizziness, or an off balance feeling. Vertigo with simultaneous migraine occurrence comes 40% of the time. Persons with recurrent vertigo and migraine headache have vestibular migraine. Some patients with vestibular migraine have migraine with aura and experience visual auras. Vestibular migraine tends to run in families.

The International Classification of Headache Disorders V 3 and the Barany Society accepted criteria for diagnosis of Vestibular Migraine in 2012.

The International Classification of Headache Disorders V 3 (ICHD3) defines Vestibular Migraine as:

Diagnostic criteria:

A) At least five episodes fulfilling criteria C and D.

B) A current or past history of Migraine without aura or Migraine with aura.

C) Vestibular symptoms of moderate or severe intensity, lasting between 5 minutes and 72 hours.

D) At least half of episodes are associated with at least one of the following three migrainous features:

1.Headache with at least two of the following four characteristics:

a) unilateral location

b) pulsating quality

c) moderate or severe intensity

d) aggravation by routine physical activity

2.photophobia and phonophobia6

3.visual aura

Previous names

Previously used terms for Vestibular Migraine: Migraine-associated vertigo/dizziness; migraine-related vestibulopathy; migrainous vertigo.

Read my Mini Book on Migraine Here.

Related statements.

Understanding Vertigo. Although usually rotary in motion with the patient at the center, vertigo can be “the perception of motion on the part of the patient.” Thus, vertigo can be non-rotary, and include a sense of linear or up and down movement.

Internal vertigo is (a false sensation of self-motion); while external vertigo is ( a false sensation that the visual surround is spinning or flowing)

Vertigo may originate in the vestibular branch of the eighth cranial nerve in the “inner ear” where it is called “peripheral” or “end organ” or in the brain--usually in the cerebellum or brain stem--where it is referred to as being “central.”

Positional vertigo occurs after a change of head position. There may be visually induced vertigo, triggered by a complex or large moving visual stimulus.

Vestibular symptoms are rated moderate when they interfere with but do not prevent daily activities and severe when daily activities cannot be continued and the patient has to lie down and restrict all activities..

Duration of episodes is highly variable. About 30% of patients have episodes lasting minutes, 30% have attacks for hours and another 30% have attacks over several days. The remaining 10% have attacks lasting seconds only, which tend to occur repeatedly during head motion, visual stimulation or after changes of head position.

Photophobia means light sensitivity, so that the patient avoids the light which worsens the headache. Migraine patients are usually sensitive to light all the time, but during a migraine, light makes it worse.

Read my article,” Migraine and Photophobia” on my website, www.doctormigraine.com.

Turn out the light!!!

Phonophobia and sonophobia are similar terms that mean sound causes the head to hurt.

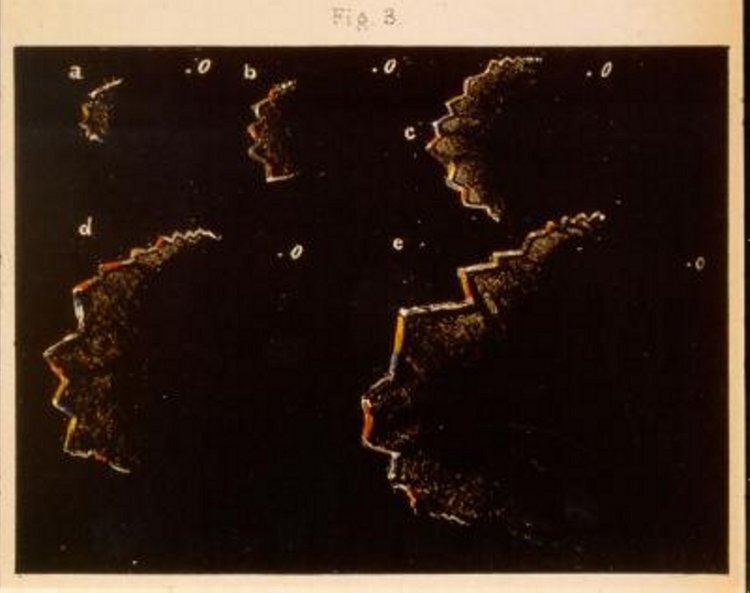

Visual auras are characterized by bright scintillating lights or zigzag lines, often with a scotoma, or blind spot, that interferes with reading. They are found with migraine with aura.

Visual auras typically expand over 5-20 minutes and last for less than 60 minutes.

Read my article, “Migraine with Aura” on my website, www.doctormigraine.com.

Zigzag Migraine aura

Examination for Vestibular Migraine. The history, physical exam, and neurologic work up including ENT and neurological consults should be normal.

Testing such as blood work, audiogram, vestibular testing, MRA scans or CAT scans of the cerebral arteries, Brain CAT scan, and MRI examinations should be normal.

Other symptoms such as short-lasting auditory symptoms, nausea, vomiting, prostration and motion sickness may be associated with Vestibular migraine, but since they also occur with other vestibular disorders, they are not included as diagnostic criteria.

Anatomy. “Vestibule” refers to the inner ear.” In Latin vestibule means “an entrance hall.” The vestibule is the central part of the bony labyrinth in the inner ear, situated medial to the eardrum (tympanic membrane), behind the cochlea, and in front of the three semicircular canals.

The chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ) mediates vomiting. It is in the medulla oblongata which is part of the brain stem. The chemoreceptor trigger zone is near the entry of the 8th auditory nerve which carries hearing and balance information.

In the inner ear the semicircular canals respond to rotational movements (angular acceleration); and the utricle and saccule respond to changes in the position of the head with respect to gravity (linear acceleration).

Migraine with and without aura-have a brain stem generator in the periaqueductal grey part of the mesencephalon near where labyrinthine fibers from the inner ear interconnect.

Migraine causes more vertigo than any other condition. The incidence of migraine in the United States is 12% while the incidence of Meniere’s disease is 0.2%.[xx] About 50% of patients with Meniere’s disease have migraine.[xxi] Neurologic practices focusing on headache report episodic vertigo in 27-42% of migraineurs.[xxii] Dizziness, vertigo, tinnitus, photophobia, hearing loss, and nystagmus may accompany migraine. Vestibular Migraine may occur without headache. Typical acute and preventive treatment for migraine may improve migrainous vertigo.[xxiii]

Migraine and vertigo have had a long relationship. Neurology textbooks for the last 50 years have all listed vertigo under the long list of symptoms associated with migraine. There is a large body of literature linking the two subjects. Many ENT and neurology articles are published every year on Migraine and Vertigo.

Dizziness is a much less precise medical term than vertigo and it has multiple causes. Dizziness does not localize to a specific area of the brain. Dizziness may be described by the patient as “light-headed, giddiness, near faintness, swimmy headed, off balance, or unsteadiness.”

Dizziness has a large group of different causes and may be due to:

Causes of Dizziness.

inner ear inflammation

hypoglycemia

electrolyte imbalance

low blood pressure

decreased cardiac output

anemia

anxiety or panic disorder

hyperventilation

medication effect

or many other causes.

Clinical Course. Vestibular Migraine is characterized by episodic symptoms of severe vertigo with or without headache which may significantly interfere with a patient’s quality of life.

The symptoms are very life disruptive when they come and often times the patient is anxious waiting for the next attack.

Vestibular Migraine is a chronic condition with attack times lasting months or years, separated by periods of normal health.

Attacks of Vestibular Migraine may be familial or sporadic. L. Luzeiro reported in Neurology Live V2:No8,2019:

“Familial occurrence has been reported in some patients with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance and decreased penetrance in men. The genetics of vestibular migraine are heterogenous and uncertain, but several studies suggest linkage to chromosome 5q35 or 22q12.”

Episodes may follow the usual migraine triggers of stress, overwork, anxiety, depression, insomnia, before or after stress (the letdown headache), or fasting.

Although all ages may be affected, it usually is worst for young adults.

Vestibular Migraine is underdiagnosed, yet it is the most common cause of recurrent spontaneous vertigo attacks.

On close questioning, most patients can differentiate between vertigo and migraine. Complicating this situation is the fact that the occurrence of dizziness in the general population is over 20%.

However, patients who have migraine with aura have significantly more dizzy spells than non-headache subjects. Dizziness is strongly associated with functional, meaning psychologic, medical problems.

Migraine and Motion sickness. Another interesting and well-known link to migraine is motion sickness which usually comes on in childhood and improves somewhat with ageing.

The symptoms of motion sickness may be nausea, dizziness, vertigo, sweating, or headache.

Commonly children experience this in the back of the car when riding. It also occurs with reading in the car, participating in amusement park rides--especially rides with fast circular motion--and on boats and airplanes.

Most studies report that about 60% of patients with migraine have motion sickness, while only 5-20% of persons without migraine get motion sickness.

Motion Sickness

Migraine and Vertigo Incidence. Medical practices that specialize in migraine find that 27-42 % of patients report episodic vertigo. About 36% of these migraineurs get vertigo when they have no headache, while many others get vertigo either just before or during the headache.

Migraine with aura patients have a higher incidence of vertigo during the headache period than those who have migraine without aura. The converse of this is that practices that specialize in vertigo find 16-32% of their patients have migraine.

Relation to Benign Paroxysmal Vertigo. Vestibular migraine may begin at any age, while benign paroxysmal vertigo is a childhood disorder.

Benign paroxysmal vertigo is diagnosed by five episodes of vertigo, occurring without warning and resolving spontaneously after minutes to hours.

Neurological examination, audiometry, vestibular functions and EEG are normal between episodes.

One-sided throbbing headache may occur during attacks but is not necessarily required.

Benign paroxysmal vertigo is a precursor of migraine which may develop more fully with ageing.

However, Vestibular migraine does not have an age limit and may be found in children and adults meeting the proper diagnostic criteria.

Vestibular Migraine and Menière’s disease. Migraine is more common in patients with Menière’s disease than in healthy controls. Many patients have Migraine, Vestibular Migraine, and Menière’s disease which may be inherited as a disease cluster.

Vestibular Migraine may have fluctuating hearing loss, tinnitus and aural pressure, but the hearing loss doesn’t progress over time to deafness which is seen on audiogram testing like with Meniere’s disease.

In the first year after onset of symptoms, differentiation between them may be challenging, since Menière’s disease can be monosymptomatic with only vestibular symptoms in the early stages of the disease.

Meniere’s Disease. The clinical course is usually of progression toward sensorineural deafness in one ear, coming through time with attacks of vertigo, tinnitus, and deafness.

Differential diagnosis of Vestibular Migraine. This includes migraine with brainstem aura, ear infection, brain stem infarct, autoimmune inner ear disease, multiple sclerosis, early Meniere’s disease, vertebrobasilar ischemia, cerebellar tumor, and Arnold-Chiari malformation.

Pathology. The relationship between Vestibular migraine and Menière’s disease is uncertain and particularly at the onset of symptoms it may be difficult to differentiate the two conditions.

Treatment of Vestibular Migraine

Acute therapy. Triptans to date have with randomized and controlled studies have been inconclusive. Many headache doctors like to use one of the benzodiazepines, which may work well. My own preference here is diazepam 5-10 mg at onset and every 4-6 hours later.

Nausea can be treated with Antivert (meclizine) 25/50 mg tablets every 4-6 hours when necessary or the Transderm scope patch which is placed behind the ear and changed every 3 days. Nausea can be treated with Phenergan (promethazine) or Zofran (odansetron) 4/8 mg sublingual every 8 hours when necessary.

Medical devices. GammaCore, a handheld, neck delivered, vagal nerve stimulator (nVNS) may be tried. Friedman, et al, Neurology (2019;93(18) 1715-1719) reported on their study using a nVNS that their study results:

“provide preliminary evidence that nVNS may provide rapid relief of vertigo and headache in acute vestibular migraine.”

Preventive therapy. Typical migraine preventive drugs such as topiramate, amitriptyline, beta blockers, and Depakote (for infertile women) may be tried, but there is little data on success.

The drugs of choice likely would be one of the CGRP drugs such as Aimovig, Emgality, or Ajovy, but again, there is no data yet

Literature Review of Vestibular Migraine

Vertigo that related to a newly recognized type of migraine was first described by Edwin Bickerstaff[v] in 1961 in his article on “Basilar Artery Migraine.” This syndrome is now termed Migraine with Brainstem Aura.

Fenichel[vi] writing in the Journal of Pediatrics in 1967 reported 2 siblings who suffered over several years from brief attacks of nausea and vertigo lasting from seconds to minutes. Later these children developed migraine with aura. Fenichel stated:

The proband of this report first presented at age two with symptoms of “benign paroxysmal vertigo.” The attacks insidiously changed in character from isolated vertigo to fairly typical migraine. Symptoms of benign paroxysmal vertigo developed in a younger brother who is now two years old. Family history reveals a high incidence for migraine in the maternal line.

In 1979 Slater[vii] writing in Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry introduced a term, “Benign Recurrent Vertigo” which consisted of episodic attacks of vertigo, no cochlear symptoms, a history of migraine, and nystagmus. Stress, lack of sleep, alcohol use, and a strong family history were also found with this group which Slater considered a migraine variant.

In 1980 Koehler[viii] presented eight young children with benign paroxysmal vertigo, a symptom complex comprised of attacks of vertigo, nystagmus, and ataxia. Follow-up studies revealed a close relationship to autonomic nervous system instability, particularly to migraine.

Moretti, at al,[ix] reported five more cases of benign paroxysmal vertigo in 1980 stressing the connection of benign recurrent vertigo to migraine. They also commented on its prevalence in women, occurrence during menstruation, but felt that there was “no time relationship between vertigo and migraine attacks.”

Kuritzky, et al,[x] reported in 1981 on “Vertigo, Motion Sickness and Migraine.” They found that patients with classical migraine(ICHD3--migraine with aura):

“reported significantly more vestibular symptoms than controls. Specifically, they had more dizzy spells and vertigo episodes not associated with the headache. They also had more frequent motion sickness spells.”

Kayan and Hood[xi] writing in Brain in 1984 on “Neuro-otological manifestations of migraine” studied vestibulocochlear derangements in 3 groups of patients: 200 migraine patients, 80 migrainous patients referred for neuro-otological examination because of their symptoms, and 116 tension headache patients who served as controls. Significant differences were established among these groups.

Migraine patients had vestibulococlear disturbances as an aura, during headache-free times, or, with highest incidence, during the headache. Fifty-nine percent of the 200 migraine patients reported vestibular and/or cochlear symptoms which were disabling for 5%.

Also 50% of the migraine patients had a history of motion sickness and 81% developed phonophobia during the headache. Persisting vestibulocochlear derangements were found in 77.5% of the 80 patients referred for neuro-otological examination. Kayan and Hood discussed “possible links between Meniere’s disease, benign paroxysmal vertigo, and migraine.”

In 1995 Abu-Arafeh and Russell[xii] wrote in Cephalalgia on “Paroxsmal vertigo as a migraine equivalent in children: a population study.” They studied the prevalence, causes, and clinical features of paroxysmal vertigo (PV) in the City of Aberdeen in 2165 children utilizing a screening questionnaire.

Children with a history of 3 episodes of vertigo were invited for clinical interview and exam. Forty-five children fulfilled the criteria for PV (prevalence rate 2.6%).

These children were noted to have features common to children with migraine along with abdominal pain, cyclical vomiting, atopy, and motion sickness. These children had a two-fold increase in the prevalence of migraine (24%) compared with the general childhood population.

The authors concluded that migraine and PV were related and that it was “reasonable to continue to regard PV as a migraine equivalent."

Buchholz and Reich[xiii] writing in 1996 in Seminars in Neurology on “The menagerie of migraine” reported that migraine may have hearing loss and vestibular dysfunction.

Lindskog in 1999[xiv] writing in 1999 in Headache on “Benign Paroxysmal Vertigo in Childhood: A Long-Term Follow-up” found no relationship between childhood Benign Positional Vertigo (BPV) and migraine in a long-term follow-up.

These researchers followed 19 children aged 5 months to 8 years diagnosed in 1975-1981 with BPV.

Follow-up was performed 13-20 years after diagnosis and 21% developed migraine which is more than expected in a normal population of that age. None of the patients had trouble with balance or vertigo at follow-up.

The authors concluded that BPV has a good outcome and is “not a general precursor of migraine.” However, most of the published articles on the subject do not agree.

Baloh[xv] writing in 1997 in Headache on “Neurotology of Migraine” stated that “Neurotology symptoms are common with migraine, yet relatively little is known about the pathophysiology of such symptoms.”

Baloh found motion sensitivity with motion sickness in 2/3 and vertigo in 1/4 of patients with migraine. He thought that sensitivity to sound (phonophobia) was the most common migraine auditory symptom, but fluctuating and permanent hearing loss may rarely occur.

Baloh noted that migraine can imitate Meniere’s disease and that so-called “vestibular Meniere’s disease” is usually associated with migraine.

Dieterich and Brandt[xvi] writing in 1999 in Journal of Neurology on “Episodic vertigo related to migraine (90 cases): vestibular migraine?” performed a retrospective study on 90 patients with episodic vertigo that could be related to migraine but that did not fulfill IHS criteria for basilar migraine. The following features were noted:

occurrence anytime in life with a peak in the 4th decade in men and a plateau between the 3rd and 5th decade in women; duration of rotational (78%) and/or to-and fro vertigo (38%) lasting from seconds to several hours, or less frequently even days. Monosymptomatic audiovestibular attacks (78%) occurred as vertigo associated with auditory symptoms in only 16%. Vertigo was not associated with headache in 32% of the patients. In the symptom-free interval 66% of the patients showed mild central ocular motor signs such as vertical (48%) and/or horizontal (22%) saccadic pursuit, gaze-evoked nystagmus (27%), moderate positional nystagmus (11%), and spontaneous nystagmus (11%). Combinations with other forms of migraine were found in 52%.

Dieterich and Brandt stated: “migraine is a relevant differential diagnosis for episodic vertigo.” They proposed using the more appropriate term “vestibular migraine.”

Radtke, et al,[xvii] writing in Neurology in 2002 on “Migraine and Meniere’s disease: is there a link?” commented that Prosper Meniere had suggested a relationship between the two episodic clinical syndromes in Paris in 1861 when he discussed the illness that bears his name.

Radtke, et al, determined the lifetime prevalence of migraine in patients with Meniere’s disease (MD) compared to sex and age-matched controls. They studied 78 patients with idiopathic unilateral or bilateral MD according to the criteria of the American Academy of Otolaryngology.

Migraine was diagnosed by phone interviews using ICHD criteria. Information concerning the concurrence of vertigo and migrainous symptoms during Meniere attacks was also collected.

The lifetime prevalence of migraine with and without aura was higher in the MD group (56%) compared to controls (25%: p<0.001). Forty-five percent of the patients with MD always experienced at least one migrainous symptom (migrainous headache, photophobia, aura symptoms) with Meniere attacks. Radtke, et al, concluded:

The lifetime prevalence of migraine is increased in patients with MD when strict diagnostic criteria for both conditions are applied. The frequent occurrence of migrainous symptoms during Ménière attacks suggests a pathophysiologic link between the two diseases. Alternatively, because migraine itself is a frequent cause of audio-vestibular symptoms, current diagnostic criteria may not differentiate between MD and migrainous vertigo.

Neuhauser and Lempert,[xviii] in Germany reported in 2004 in Cephalalgia on “Vertigo and dizziness related to migraine: a diagnostic challenge.” These authors stated:

Migrainous vertigo (MV) is a vestibular syndrome caused by migraine and presents with attacks of spontaneous or positional vertigo lasting seconds to days and migrainous symptoms during the attack. MV is the most common cause of spontaneous recurrent vertigo and is presently not included in the International Headache Society classification of migraine. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) and Ménière's disease (MD) are statistically related to migraine, but the possible pathogenetic links have not been established. Moreover, migraineurs suffer from motion sickness more often than controls.

Neuhauser, et al,[xix] writing in 2006 in Neurology on “Migrainous vertigo: Prevalence and impact on quality of life,” studied the epidemiology of migrainous vertigo (MV) in the general population by assessing prevalence, clinical features, comorbid conditions, quality of life, and health care utilization.

They screened 4,869 adults for dizziness and vertigo and then followed up with validated neurotologic telephone interviews. They used the diagnostic criteria for benign recurrent vertigo and migraine according to the IHS. They reported a lifetime prevalence of MV of 0.98% and a 12-month prevalence of 0.89%.

Spontaneous rotational vertigo was reported by 67% of patients with MV while 24% had positional vertigo. Twenty-four percent always experienced headaches with their vertigo. Neuhauser, et al, concluded:

Migrainous vertigo is relatively common but under diagnosed in the general population and has considerable personal and healthcare impact.

Check out my Big Book on Migraine Here.

[i] Merritt HH. A Textbook of Neurology. 1973.Fifth Edition. Lea & Febiger.

Philadelphia. Page:732.

[ii] Kuritzky A, Ziegler DK, Hassanein R. Vertigo, Motion Sickness and Migraine. Headache. 1981;21:227-231.

[iii] Hain TC. Migraine Associated Vertigo (MAV) Adapted from a lecture handout given for the seminar “Recent advances in the treatment of Dizziness” American Academy of Neurology, 1997 and “Migraine Vs Meniere’s”, at the American Academy of Otolaryngology meeting. 1999-2001.

[iv] Hain TC. Migraine Associated Vertigo (MAV) Adapted from a lecture handout given for the seminar “Recent advances in the treatment of Dizziness” American Academy of Neurology, 1997 and “Migraine Vs Meniere’s”, at the American Academy of Otolaryngology meeting. 1999-2001.

[v] Bickerstaff ER. Basilar Artery Migraine. Lancet. 1961;1:15-17.

[vi] Fenichel GM. Migraine as a cause of benign paroxysmal vertigo of childhood. J Pediatr. 1967;71:114-115.

[vii] Slater R. Benign recurrent vertigo. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1979;42:363.

[viii] Koehler B. Benign paroxysmal vertigo of childhood: A migraine equivalent. European Journal of Pediatrics. 1980;134(2):149-151.

[ix] Moretti G, Manzoni G.C. Caffarra P, Parma M. "Benign Recurrent Vertigo" and Its Connection with Migraine. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 1980;20(6):344–346.

[x] Kuritzky A, Ziegler DK, Hassanein R. Vertigo, Motion Sickness and Migraine. Headache. 1981;21:227-231.

[xi] Kayan A, Hood JD. Neuro-otological manifestations of migraine. Brain. 1984;107(Pt4):1123-1142.

[xii] Abu-Arafeh I, Russell G. Paroxysmal vertigo as a migraine equivalent in children: a population-based study. Cephalalgia. 1995;15(1):22–25.

[xiii] Buchholz DW, Reich SG. The menagerie of migraine. Seminars in Neurology. 1996;16(1):83-93.

[xiv] Lindskog U, Ödkvist L, Noaksson L, Wallquist J. Benign Paroxysmal Vertigo in Childhood: A Long-term Follow-up. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 1999;39(1),33–37.

[xv] Baloh RW. Neurotology of Migraine. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 1997; 37 (10), 615–621.

[xvi] Dieterich M, Brandt T. Episodic vertigo related to migraine (90 cases): vestibular migraine? Journal of Neurology. 1999;246(10):883-892.

[xvii] Radtke R, Lempert T, Gresty MA, Brookes GB, Bronstein AM, Neuhauser H. Migraine and Meniere’s disease. Is there a link? Neurology. 2002;59:1700-1704.

[xviii] Neuhauser H, Lempert T. Vertigo and dizziness related to migraine: a diagnostic challenge. Cephalalgia. 2004;24 (2):83–91.

[xix] Neuhauser HK, Radtke A, von Brevern M, Feldmann M, Lezius F, Ziese T, Lempert T. Migrainous vertigo: Prevalence and impact on quality of life. Neurology. 2006;67:1028-1033.

[xx] Wladislavosky-Waserman P, Facer G, et al. Meniere's disease: a 30-year epidemiologic and clinical study in Rochester, MN, 1951-1980. 1996. Laryngoscope 94:1098-1102.

[xxi] Radtke R, Lempert T, Gresty MA, Brookes GB, Bronstein AM, Neuhauser H. Migraine and Meniere’s disease. Is there a link? Neurology. 2002;59:1700-1704.

[xxii] http://www.dizziness-and-balance.com/disorders/central/migraine/mav.html

[xxiii] Ibid.

Huang TC, et al, Cephalalgia. 2020 Jan;40(1):107-121. doi: 10.1177/0333102419869317. Epub 2019 Aug 8, Vestibular migraine: An update on current understanding and future directions.

Marianne Dieterich, J Neurol. 2016; 263: 82–89. Vestibular migraine: the most frequent entity of episodic vertigo

Isabel Luzeiro, et al, Behavioral Neurology, Volume 2016 |Article ID 6179805 | 11 pages | https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/6179805, Vestibular Migraine: Clinical Challenges and Opportunities for Multidisciplinarity

Beh SC, Friedman D, Neurology. 2019 Oct 29;93(18):e1715-e1719. Acute vestibular migraine treatment with noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation.

This site is owned and operated by Internet School LLC, a limited liability company headquartered in Dallas, Texas, USA. Internet School LLC is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com. Although this site provides information about various medical conditions, the reader is directed to his own treating physician for medical treatment.

All the best.

Follow me at: www.doctormigraine.com, Pinterest, Amazon books, Podcasts, and YouTube.

Britt Talley Daniel MD